Vitamin D Testing - CAM 126

Description

Vitamin D is a precursor to steroid hormones and plays a key role in calcium absorption and mineral metabolism. Vitamin D promotes enterocyte differentiation and the intestinal absorption of calcium. Other effects include a lesser stimulation of intestinal phosphate absorption, suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) release, regulation of osteoblast function, osteoclast activation, and bone resorption (Pazirandeh & Burns, 2023).

Vitamin D is present in nature in two major forms. Ergocalciferol, or vitamin D2, is found in fatty fish (e.g., salmon and tuna) and egg yolks, although very few foods naturally contain significant amounts of vitamin D. Cholecalciferol, or vitamin D3, is synthesized in the skin via exposure to ultraviolet radiation present in sunlight. Some foods are also fortified with vitamin D, most notably milk and cereals (Sahota, 2014).

Though the risk of vitamin D deficiency can differ by age, sex, and race and ethnicity, major risk factors for vitamin D deficiency include inadequate sunlight exposure, inadequate dietary intake of vitamin D-containing foods, and malabsorption syndromes, such as Crohn’s disease and celiac disease (Dedeoglu et al., 2014; Looker et al., 2011).

Regulatory Status

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

A search of the FDA Device database on May 26, 2022, for “vitamin D” yielded 42 results. Additionally, many labs have developed specific tests that they must validate and perform in house. These laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA ’88). As an LDT, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request:

- For individuals with an underlying disease or condition which is specifically associated with vitamin D deficiency or decreased bone density (see Note 1) or for individuals suspected of hypervitaminosis of Vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D serum testing is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- As part of the total 25-hydroxyvitamin D analysis, testing for D2 and D3 fractions of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For individuals who have documented vitamin D deficiency, repeat testing for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at least 12 weeks after the initiation of vitamin D supplementation therapy is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY with the following restrictions:

- Twice per year testing for the monitoring of supplementation therapy, until the therapeutic goal has been achieved.

- Annual testing once the therapeutic range has been achieved.

- For the evaluation or treatment of conditions that are associated with defects in vitamin D metabolism (see Note 2), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D serum testing is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- The following testing is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- Measurement of serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D to screen for vitamin D deficiency.

- Routine screening for vitamin D deficiency with serum testing in asymptomatic individuals and/or during general encounters

NOTES:

Note 1: Indications for serum measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are as follows:

- Biliary cirrhosis and other specified disorders of the biliary tract

- Blind loop syndrome

- Celiac disease

- Coronary artery disease in individuals where risk of disease progression is being considered against benefits of chronic vitamin D and calcium therapy

- Dermatomyositis

- Eating disorders

- Having undergone, or for those who have been scheduled for, bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch

- Hypercalcemia, hypocalcemia, or other disorders of calcium metabolism

- Hyperparathyroidism or hypoparathyroidism

- Individuals receiving hyperalimentation

- Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis)

- Intestinal malabsorption

- Liver cirrhosis

- Long term use of anticonvulsants, glucocorticoids and other medications known to lower vitamin D levels

- Malnutrition

- Myalgia and other myositis not specified

- Myopathy related to endocrine diseases

- Neoplastic hematologic disorders

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Osteomalacia

- Osteopetrosis

- Osteoporosis

- Pancreatic steatorrhea

- Primary or miliary tuberculosis

- Psoriasis

- Regional enteritis

- Renal, ureteral, or urinary calculus

- Rickets

- Sarcoidosis

- Stage III-V Chronic Kidney Disease and End Stage Renal Disease

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

Note 2: Indications for serum testing of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D are as follows:

- Disorders of calcium metabolism

- Familial hypophosphatemia

- Fanconi syndrome

- Hyperparathyroidism or hypoparathyroidism

- Individuals receiving hyperalimentation

- Neonatal hypocalcemia

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Osteomalacia

- Osteopetrosis

- Primary or miliary tuberculosis

- Renal, ureteral, or urinary calculus

- Rickets

- Sarcoidosis

- Stage III-V Chronic Kidney Disease and End Stage Renal Disease

Table of Terminology

| Term |

Definition |

| 25(OH)D |

25-Hydroxyvitamin D |

| 25OHD |

25-Hydroxyvitamin D |

| AACE |

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists |

| ACE |

American College of Endocrinology |

| AAP |

American Academy of Pediatrics |

| ACOG |

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| BMD |

Bone mineral density |

| BPD |

Biliopancreatic diversion |

| CDC |

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CLIA ’88 |

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 |

| CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| DS |

Duodenal switch |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ES |

Endocrine Society |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| HPLC |

High-performance liquid chromatography |

| IDS |

Immunodiagnostic Systems |

| IOM |

Institute of Medicine |

| IU |

International unit |

| LAGB |

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding |

| LC/MS |

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| LDTs |

Laboratory developed tests |

| LSG |

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome |

| MEWS |

Modified Early Warning Score |

| MS |

Mass spectrometry |

| NHANES |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| PTH |

Parathyroid hormone |

| RIA |

Radioimmunoassay |

| ROS |

Royal Osteoporosis Society |

| RYGB |

Rouxen-Y gastric bypass |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SPF |

Sun protection factor |

| THIN |

The Health Improvement Network |

| USPSTF |

United States Preventive Services Task Force |

| UVB |

Ultraviolet B |

| VDSCP |

Vitamin D Standardization Certification Program |

Rationale

Vitamin D is an important nutrient that helps the body absorb calcium and maintain adequate bone strength. In order to be used in the metabolic process, vitamin D that is consumed or formed in the skin must first be activated via the addition of hydroxyl groups. Two forms of activated vitamin D are found in human circulation: 25-hydroxyvitamin D (calcidiol or 25OHD) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol). 25-hydroxyvitamin D is the predominant and most stable form, but 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is the metabolically active form. The initial activation step occurs in the liver, where 25OHD is synthesized, and the second hydroxyl group is added in the kidney, creating the fully activated 1,25-dihdroxy form (Sahota, 2014).

25-hydroxyvitamin D has a half-life of 15 days in the circulation, whereas 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D has a much shorter circulating half-life of 15 hours. Consequently, measurement of serum 25OHD is generally accepted as the preferred test to evaluate an individual’s vitamin D status despite lack of standardization between methods and laboratories (Glendenning & Inderjeeth, 2012; Sahota, 2014; Scott et al., 2015).

Vitamin D deficiency typically is defined as a serum 25OHD level less than 20 ng/ml, and certain organizations consider <30 ng/ml as insufficient. Trials of vitamin D supplementation (Chapuy et al., 2002; Dawson-Hughes et al., 1997; Sanders et al., 2010; Trivedi et al., 2003) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) systematic review (Ross et al., 2011) recommend maintaining the serum 25OHD concentration between 20 and 40 ng/mL (50 to 100 nmol/L), whereas other experts favor maintaining 25OHD levels between 30 and 50 ng/mL (75 to 125 nmol/L). Experts agree that levels lower than 20 ng/mL are suboptimal for skeletal health. The optimal serum 25OHD concentrations for extra-skeletal health have not been established (Dawson-Hughes, 2024). Approximately 15% of the U.S. pediatric population suffers from either vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency. Limited sun exposure and the use of sunscreen compromises production of vitamin D, contributing to low 25OHD levels. “UVB absorption is blocked by artificial sunscreens, and sunscreens with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 30 can decrease vitamin D synthetic capacity by as much as 95 percent” (Madhusmita, 2024). Also, “vitamin D deficiency has been reported in dark-skinned immigrants from warm climates to cold climates in North America and Europe” (Dawson-Hughes, 2023). For example, a study by Awumey and colleagues found that Asian Indians who immigrated to the U.S. were considered vitamin D insufficient or deficient even after the administration of 25OHD. “Thus, Asian Indians residing in the U.S. are at risk for developing vitamin D deficiency, rickets, and osteomalacia” (Awumey et al., 1998).

Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with important short and long term health effects, such as rickets, osteomalacia, and the risk of osteoporosis (Sahota, 2014). Rickets in children can result in skeletal deformities. To prevent nutritional rickets in infants, vitamin D supplementation is recommended at 400 IU/day; personalized dosages are possible and would require 25OHD testing (Zittermann et al., 2019). In adults, osteomalacia can result in muscular weakness, bone weakness, and osteoporosis which leads to an increased risk for falls and fractures (Granado-Lorencio et al., 2016).

A role for vitamin D has been suggested in several other conditions and metabolic processes including, but not limited to, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and preeclampsia. While vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with several cancer types, inconsistencies cause discrepancies in suggested treatment methods; currently, no official institutional guidelines recommend a dietary vitamin D supplementation for cancer prevention (McNamara & Rosenberger, 2019). 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) is the accepted biomarker of circulating vitamin D, and in utilization of this biomarker, researchers have reported an association between a high vitamin D production rate and a lowered risk of colorectal cancer (Weinstein et al., 2015). Further, low concentrations of 25OHD have been associated with a high risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality, suggesting that patients deficient in vitamin D have an increased risk in developing cardiovascular disease (Crowe et al., 2019). However, conclusive evidence for the role of vitamin D in these conditions is not available (Aspray et al., 2014; Ross et al., 2011). Based on controversial evidence, researchers continue to emphasize the fact that vitamin D supplementation is not an accepted prevention method for cardiac events or cancer (Ebell, 2019).

Certain other conditions may impact an individual’s ability to absorb or activate vitamin D, thereby resulting in vitamin D deficiency. These include, but are not limited to, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, liver cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, and bariatric surgery. Since Vitamin D is fat soluble, any impact on fat absorption or storage may affect circulating vitamin D levels (Dawson-Hughes, 2023; Fletcher et al., 2019).

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), routine dietary supplementation with vitamin D is recommended for most individuals. While there are no differences regarding gender and recommended daily dose of vitamin D, there are differences depending on age. The IOM recommends a dietary allowance of 600 IU for individuals up to 70 years old, and 800 IU for individuals older than 70 (Ross et al., 2011), although these recommendations have been met with some criticism as being too low to adequately impact vitamin D levels in some individuals. The USPSTF recommends against daily supplementation with 400 IU or less of vitamin D3 and 1000 mg or less of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal individuals (Moyer, 2013).

Vitamin D toxicity is very rare and occurs only when levels of 25OHD are > 500 nmol/L [> 200 ng/mL], which is well above the level considered sufficient. Vitamin D toxicity may cause hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, renal stones, and renal calcification with renal failure (Moyer, 2013). Additional research suggests that excess 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 aggravates tubulointerstitial injury (Kusunoki et al., 2015).

Insource Diagnostics has developed two similar quantitative laboratory developed tests (LDTs) termed Sensieva VenaTM 25OH Vitamin D2/D3 and Droplet 25OH Vitamin D2/D3. These assays utilize liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to measure both D2 and D3. The LC/MS/MS assessment technique is the apparent gold standard for vitamin D2 and D3 measurement, and is the only currently available method to measure both vitamins individually. These assays may assist in the measurement of several ailments related to abnormal vitamin D levels including parathyroid function, dietary absorption, calcium metabolism, and vitamin D treatment effectiveness; serum, plasma and blood microsamples can be utilized for these tests. The 20uL serum/plasma method of the SensievaTM 25OH Vitamin D2/D3 LDT was approved by the CDC’s VDSCP in 2017 – 2018 (CDC, 2019). This test is no longer certified by the CDC’s VDSCP and as of May 2020 Insource Diagnostics website has been removed. Therefore, it is unclear if this test is still available.

Analytical Validity

Serum or plasma concentration of 25OHD can be measured using several assays, including ELISA, radioimmunoassay (RIA), mass spectrometry, and HPLC. Assays using LC-MS/MS can differentiate between D¬2 and D3. These methods “can individually quantitate and report both analytes, in addition to providing a total 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration” (Krasowski, 2011). RIA-based assays for 25OHD can have intra- and inter-assay variations of 8% – 15%, and the Immunodiagnostic Systems (IDS)-developed RIA has a reported 100% specificity for D3 and 75% for D2 (Holick, 2009). “For most HPLC and LC-MS/MS methods extraction and procedural losses are corrected for by the inclusion of an internal standard which, in part, may account for higher results compared to immunoassay” (Wallace et al., 2010). Even though LC-MS/MS is considered to be the gold standard of measuring 25OHD and its metabolites, only approximately 20% of labs report using it (Avenell et al., 2018). One study reports that 46% of samples measured using LC-MS/MS were classified as vitamin D-deficient whereas, when the samples were measured using an immunoassay method, 69% were vitamin D-deficient (< 30 nmol/L) (Annema et al., 2018).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have developed a vitamin D standardization certification program (VDSCP). This program helps to ensure that all LDT vitamin D tests are accurate and reliable by evaluating the performance and overall reliability of these assessments over time, supplying reference measurements for both 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, and providing technical support to additional programs and studies (CDC, 2017).

Due to the great variability among the different assays used to measure vitamin D levels, the VDSCP was created. Interassay variability yields an inadequate basis to establish if 25OHD increases or decreases the risk of non-skeletal diseases and hampers the development of evidence-based guidelines and policies (Sempos & Binkley, 2020). VDSCP studies can either be retrospective or prospective; therefore, standardization of national nutrition survey data may be performed. For example, it was originally thought, based on reports from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), that there had been a dramatic decline in mean 25OHD levels in the US population from 1990 to the period 2001 – 2004. DiaSorin Radioimmunoassay was used to measure 25OHD levels in these surveys. However, after standardizing the results using VDSCP methods, it was found that the mean 25OHD levels were stable from 1990 – 2004 (Sempos et al., 2018). The VDSCP program established four steps to achieve standardization, as described by:

- “Fit for use … means that assay chosen will perform appropriately and provide standardised measurements in the patient/study populations in the conditions for which it will be used … [as] some immunoassays do not function appropriately in all patient populations.

- [Assay is] Certified by the CDC Vitamin D Standardization Certification Program as being standardised and having an appropriate measurement range or be a documented standardised laboratory-developed HPLC or LC-MS/MS assay with an appropriate measurement range … see which ones are currently, or have been in the past, certified by the CDC as meeting VDSP performance criteria of having a total (coefficient of variation) CV ≤ 10% and a mean bias with the range of –5 to +5%. ... VDSP recommends using an assay that does have an appropriate measurement range for the population it will be used in; for example, it should be able to measure 25(OH)D in persons who are deficient.

- Appropriate level of assay precision and accuracy … it has been recommended that a standardised LC-MS/MS assay be selected.

- [The assay] Meets VDSP assay standardisation criteria in your ‘hands’ or laboratory. … We recommend a testing period in order to verify that an immunoassay is standardized especially since there is generally very little an individual laboratory can do to ‘calibrate’ an immunoassay” (Sempos & Binkley, 2020).

Clinical Utility and Validity

A retrospective study of 32,363 tests of serum 25OHD found that a significant proportion of the lab requests were unjustified by medical criteria, and “that clinical and biochemical criteria may be necessary to justify vitamin D testing but not sufficient to indicate the presence of vitamin D deficiency” (Granado-Lorencio et al., 2016).

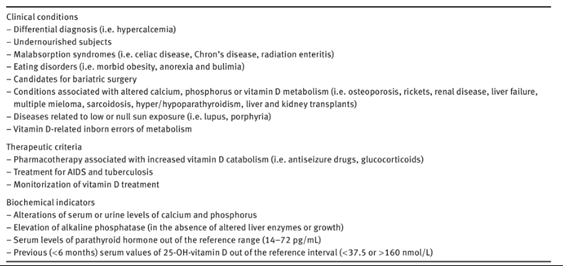

The table below lists the criteria used for vitamin D testing in the study by Granado and colleagues (Granado-Lorencio et al., 2016).

A meta-analysis study by Bolland et al. (2018) of 81 randomized controlled trials with a combined total of 53,537 participants measured the effects, if any, vitamin D supplementation had on fractures, falls, and bone density. They found that there was no clinically relevant difference in bone mineral density at any site between the control and experimental groups; moreover, “for total fracture and falls, the effect estimate lay within the futility boundary for relative risks of 15%, 10%, 7.5%, and 5% (total fracture only), suggesting that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce fractures or falls by these amounts. Our findings suggest that vitamin D supplementation does not prevent fractures or falls or clinically meaningful effects on bone mineral density. There were no differences between the effects of higher and lower doses of vitamin D. There is little justification to use vitamin D supplements to maintain or improve musculoskeletal health. This conclusion should be reflected in clinical guidelines” (Bolland et al., 2018).

A prospective study by Hao et al. (2020) aims to determine whether 25OHD levels is associated with mortality or the ability to walk in a patient cohort after hip fracture surgery. Each year, 319,000 elderly patients, are hospitalized for hip fractures (CDC, 2024). In this study, 290 elderly patients with hip fractures were included, in which patients with 25OHD deficiency (<12 ng/ml) were used as the reference group. They observed a 56% – 64% increased rate of walking in patients who had 25OHD levels > 12 ng/ml at 30 days and 60 days after hip fracture surgery compared with 35% for patients able to walk 30 days postoperatively who had 25OHD levels < 12 ng/ml (Hao et al., 2020). It is important to note that only the preoperative 25OHD levels accurately reflect the patient’s ability to walk after 30 days, and the postoperative vitamin D status is not related and should not be used to determine clinical or nutritional interventions. Holick (2020) releases a call for action, discussing the data collected by Hao, to establish guidelines which will assess vitamin D status as needed for patients with hip fracture. Holick suggests that “patients aged ≥50 y presenting with fractures, especially those with hip fracture, should be evaluated at intake for their vitamin D status. Consideration should be made to provide vitamin D supplementation if dietary/supplemental intake or blood concentrations of 25(OH)D suggest deficiency” (Holick, 2020).

Another randomized clinical trial administered by Scragg et al. (2017) provided a monthly high dose of vitamin D to 5,108 participants in order to determine if a relationship exists between increased vitamin D levels and cardiovascular disease prevention. This double-blind trial was placebo-controlled; participants were given an initial dose of 200,000 IU of vitamin D, and then each month after for a range of 2.5 – 4.2 years were given 100,000 IU of vitamin D (Scragg et al., 2017). Results showed that in a random sample of 438 participants, cardiovascular disease occurred in 11.8% of patients who received vitamin D supplements and in 11.5% of patients who received placebos. This suggests that vitamin D administration does not prevent cardiovascular disease and should not be used for this purpose (Scragg et al., 2017).

Zhao et al. (2015) carried out a study within a primary care cohort the UK. Vitamin D results of 9,460 (74%) first tests and 3,263 (26%) retests were analyzed. Of the first-test results, 42% of patients were deficient. The authors noted a marked increase in Vitamin D testing over the six-year period of the study. However, a significant amount of the test requests were retests. The authors cautioned against over-testing for Vitamin D too soon, before serum levels could show adequate response: “A significant proportion of requests were retests. Despite guidelines recommending retesting after three to six months, 20% of retests were performed within three months. Our results suggest that retesting soon after intervention may not allow sufficient time for serum levels to respond. By contrast, retesting within four weeks of a large loading dose may give a false picture of over repletion” (Zhao et al., 2015).

Regarding pregnancy, vitamin D deficiency is common around the world and threatens fetal health and growth. Results from 203 Indonesian pregnant individuals who were followed from their first trimester until delivery showed astronomical vitamin D deficiency rates at approximately 75% (Yuniati et al., 2019). Data collected from these individuals included maternal demography, bloodwork to test ferritin levels, 25(OH) vitamin D results in their first trimester, and the final birthweight of the child after delivery. Final results did not show any association between ferritin, hemoglobin level, and vitamin D in either the first trimester of pregnancy or in the final birthweight of the neonates after delivery; however, the authors suggest that other unknown variables may be important and that nutritional supplementation during pregnancy is still vital (Yuniati et al., 2019).

Research has also been conducted on the association of 25(OH)D levels and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ribeiro et al. (2021) conducted a retrospective cohort study on 1638 patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection and found that “previous insufficient 25(OH)D (< 30ng/mL) concentration and high total cholesterol were associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among adults > 48 y in the study population.” This may be attributable to the role that vitamin D serves in the immune system and its anti-viral activity through autophagy, as well as its high expression in cells of the lungs, thus rendering those with lower levels of 25(OH)D more susceptible to infection without these defenses (Ul Afshan et al., 2021).

Szerszeń et al. (2022) also investigated the possible correlation between the immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D and the incidence and progression of COVID. From a sample of 505 patients, they quantified serum 25OHD and analyzed each patient’s COVID severity through the serum Vitamin Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), “which includes respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and state of consciousness,” along with the days spent in the intensive care unit. The results demonstrated that there was no difference in 25OHD concentration between those with and without COVID as determined by PCR and no correlation between serum 25OHD “in the COVID(+) group and the need for and time spend in the ICU as well as the MEWS score.” However, multivariate analyses did show a positive correlation between the need for oxygen therapy and lower 25OHD concentration. This signifies the evolving role of vitamin D in and how low serum levels may aid in predicting more complicated treatment courses.

On the other hand, Javed et al. (2020) found that “high serum levels of vitamin D are associated with a lower risk of incidence and progression of [colorectal cancer].” This could make vitamin D testing crucial to identify possible future therapeutic modalities for patients with both low serum vitamin D and colorectal cancer. Like its mechanisms that hinder SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as being pro-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory, vitamin D has been shown to “decrease growth and differentiation of colon epithelial cells.” With more large-scale human trials, testing and treatment using vitamin D can become more widely applicable.

It is also known that decreased vitamin D levels are associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), though the mechanisms have not been fully elucidated (Nielsen et al., 2019; Vernia et al., 2022). Studies further suggest that vitamin D supplementation may positively impact the course of IBD, highlighting the utility of vitamin D testing in this patient population. It has been suggested that a daily dose of 2000 IU correlates with improvements in IBD symptoms and patient quality of life (El Amrousy et al., 2021; Goulart & Barbalho, 2022).

The Endocrine Society (ES)

In 2011, the Endocrine Society recommended serum testing of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for evaluation of vitamin D status in individuals who are at risk of deficiency, including those with osteoporosis, obesity, or a history of falls. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D testing was not recommended for screening of at-risk individuals, due to its very short half-life in circulation, but is recommended for a few conditions in which formation of the 1,25-dihydroxy form may be impaired (Holick et al., 2011).

In 2024, the ES updated their guideline on Vitamin D testing and focused primarily on 25(OH)D serum testing without recommendations on 1,25-dihodroxyvitamin D testing. The ES reiterated the lack of clinical trial evidence supporting routine screening for 25(OH)D and used this evidence to reaffirm a position against routine screening of Vitamin D in the general population. “No clinical trial evidence was found to support routine screening for 25(OH)D in the general population, nor in those with obesity or dark complexion, and there was no clear evidence defining the optimal target level of 25(OH)D required for disease prevention in the populations considered; thus, the panel suggests against routine 25(OH)D testing in all populations considered.” One notable difference between the 2011 and 2024 guideline is the changed position on screening Vitamin D in adults with obesity.

Pertaining to Vitamin D testing, the ES recommends the following:

- “In the general adult population younger than age 50 years, we suggest against routine 25(OH)D testing.”

- “In the general population aged 50 to 74 years, we suggest against routine 25(OH)D testing.”

- “In the general population aged 75 years and older, we suggest against routine testing for 25(OH)D levels.”

- “During pregnancy, we suggest against routine 25(OH)D testing.”

- “In healthy adults, we suggest against routine screening for 25(OH)D levels.”

- “In adults with dark complexion, we suggest against routine screening for 25(OH)D levels.”

- “In adults with obesity, we suggest against routine screening for 25(OH)D levels” (Demay et al., 2024).

Institute of Medicine (IOM)

After an extensive evaluation of published studies and testimony from investigators, the Institute of Medicine determined that supplementation with vitamin D is appropriate; however, guidelines regarding the use of serum markers of vitamin D status for medical management of individual patients and for screening were beyond the scope of the Committee’s charge, and evidence-based consensus guidelines are not available (Ross et al., 2011).

National Health Service (NHS) Clinical Commissioning Group

In “Guidelines for the Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency” the UK National Health Service notes that re-testing for Vitamin D levels before three months of supplementation is not advised as “vitamin D has a relatively long half-life, levels will take approximately three months to reach steady state after loading dose or maintenance treatment” (NHS, 2016).

Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS)

The Royal Osteoporosis Society (formerly known as the National Osteoporosis Society) recommends the measurement of serum 25 (OH) vitamin D (25OHD) to estimate vitamin D status in the following clinical scenarios: bone diseases that may be improved with vitamin D treatment; bone diseases, prior to specific treatment where correcting vitamin D deficiency is appropriate; musculoskeletal symptoms that could be attributed to vitamin D deficiency. The guideline also states that routine vitamin D testing is unnecessary where vitamin D supplementation with an oral antiresorptive treatment is already planned and sets the following serum 25OHD thresholds: < 25 nmol/l is deficient; 25 – 50 nmol/l may be inadequate in some people; > 50 nmol/l is sufficient for almost the whole population (Royal Osteoporosis Society, 2020).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

In a statement on gynecologic care for adolescents and individuals with eating disorders, ACOG specified that in patients with low bone mineral density (BMD), “A patient’s 25-hydroxy vitamin D level should be checked and, if less than 30 ng per mL, the patient should be given supplementation for 6 – 8 weeks in the form of 2,000 international units daily or 50,000 international units weekly” (Wassenaar et al., 2018). Reaffirmed in 2021.

Concerning screening for vitamin D deficiency, ACOG states that there is insufficient support currently to recommend screening for all pregnant individuals for vitamin D deficiency but that “maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels can be considered and should be interpreted in the context of the individual clinical circumstance” (ACOG, 2011). Additionally, ACOG mentions that, while there is no broad consensus on the ideal vitamin D level to maintain optimal health, most guidelines agree that a serum level of at least 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) is needed to avoid bone problems. Reaffirmed in 2021 (ACOG, 2011).

United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF published their recommendation concerning screening of vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults in 2021. “The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults” (I statement) (USPSTF, 2021).

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

For patients undergoing Rouxen-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy, or biliopancreatic diversion either with or without duodenal switch (BPD/DS), a baseline evaluation for vitamin D deficiency and a postoperative evaluation is recommended (Mechanick et al., 2019).

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) / American College of Endocrinology (ACE)

The 2020 guideline addressed fundamental measures for bone health for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. The following statements apply to Vitamin D:

- “Measure serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) in patients who are at risk for vitamin D insufficiency, particularly those with osteoporosis (Grade B; BEL 2).”

- “Maintain serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) ≥30 ng/mL in patients with osteoporosis (preferable range, 30 to 50 ng/mL) (Grade A; BEL 1).”

- “Supplement with vitamin D3 if needed, with a daily dose of 1,000 to 2,000 international units (IU) typically required to maintain an optimal serum 25(OH)D level (Grade A; BEL 1).”

- “Higher doses of vitamin D3 may be necessary in patients with present factors such as obesity, malabsorption, and older age (Grade A; BEL 1)” (Camacho et al., 2020).

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

“Evidence is insufficient to recommend universal screening for vitamin D deficiency. … In the absence of evidence supporting the role of screening healthy individuals at risk for vitamin D deficiency in reducing fracture risk and the potential costs involved, the present AAP report advises screening for vitamin D deficiency only in children and adolescents with conditions associated with reduced bone mass and/or recurrent low-impact fractures. More evidence is needed before recommendations can be made regarding screening of healthy black and Hispanic children or children with obesity. The recommended screening is measuring serum 25-OH-D concentration, and it is important to be sure this test is chosen instead of measurement of the 1,25-OH2-D concentration, which has little, if any, predictive value related to bone health” (Golden & Abrams, 2014).

Through the Choosing Wisely initiative, the AAP advises against routine vitamin D screening in otherwise healthy children, including those who are overweight or obese. Current evidence does not support the necessity of such screening, aligning with global recommendations against population-based screening for vitamin D deficiency. Instead, the AAFP recommends vitamin D supplements for children with insufficient dietary intake (AAP, 2022)

References

- AAP. (2022). Section on Endocrinology: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/Choosing%20Wisely/CWEndocrinology.pdf

- ACOG. (2011). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 495: Vitamin D: Screening and supplementation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 118(1), 197-198. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f06b

- Annema, W., Nowak, A., von Eckardstein, A., & Saleh, L. (2018). Evaluation of the new restandardized Abbott Architect 25-OH Vitamin D assay in vitamin D-insufficient and vitamin D-supplemented individuals. J Clin Lab Anal, 32(4), e22328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22328

- Aspray, T. J., Bowring, C., Fraser, W., Gittoes, N., Javaid, M. K., Macdonald, H., Patel, S., Selby, P., Tanna, N., & Francis, R. M. (2014). National Osteoporosis Society vitamin D guideline summary. Age Ageing, 43(5), 592-595. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu093

- Avenell, A., Bolland, M. J., & Grey, A. (2018). 25-Hydroxyvitamin D - Should labs be measuring it? Ann Clin Biochem, 4563218796858. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563218796858

- Awumey, E. M., Mitra, D. A., Hollis, B. W., Kumar, R., & Bell, N. H. (1998). Vitamin D metabolism is altered in Asian Indians in the southern United States: a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 83(1), 169-173. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.83.1.4514

- Bolland, M. J., Grey, A., & Avenell, A. (2018). Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(18)30265-1

- Camacho, P. M., Petak, S. M., Binkley, N., Diab, D. L., Eldeiry, L. S., Farooki, A., Harris, S. T., Hurley, D. L., Kelly, J., Lewiecki, E. M., Pessah-Pollack, R., McClung, M., Wimalawansa, S. J., & Watts, N. B. (2020). AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS/AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF POSTMENOPAUSAL OSTEOPOROSIS-2020 UPDATE. Endocr Pract, 26(Suppl 1), 1-46. https://doi.org/10.4158/gl-2020-0524suppl

- CDC. (2017). VDSCP: Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program. VDSCP: Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program

- CDC. (2019). CDC Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program. https://www.cdc.gov/labstandards/pdf/hs/CDC_Certified_Vitamin_D_Procedures-508.pdf

- CDC. (2024). Facts: Falls Are Serious and Costly. https://www.cdc.gov/falls/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html

- Chapuy, M. C., Pamphile, R., Paris, E., Kempf, C., Schlichting, M., Arnaud, S., Garnero, P., & Meunier, P. J. (2002). Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: the Decalyos II study. Osteoporos Int, 13(3), 257-264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980200023

- Crowe, F. L., Thayakaran, R., Gittoes, N., Hewison, M., Thomas, G. N., Scragg, R., & Nirantharakumar, K. (2019). Non-linear associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: Results from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 195, 105480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105480

- Dawson-Hughes, B. (2023, May 16). Causes of vitamin D deficiency and resistance. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/causes-of-vitamin-d-deficiency-and-resistance

- Dawson-Hughes, B. (2024, July 29, 2024). Vitamin D deficiency in adults: Definition, clinical manifestations, and treatment. UptoDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitamin-d-deficiency-in-adults-definition-clinical-manifestations-and-treatment

- Dawson-Hughes, B., Harris, S. S., Krall, E. A., & Dallal, G. E. (1997). Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med, 337(10), 670-676. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199709043371003

- Dedeoglu, M., Garip, Y., & Bodur, H. (2014). Osteomalacia in Crohn's disease. Arch Osteoporos, 9, 177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-014-0177-0

- Demay, M. B., Pittas, A. G., Bikle, D. D., Diab, D. L., Kiely, M. E., Lazaretti-Castro, M., Lips, P., Mitchell, D. M., Murad, M. H., Powers, S., Rao, S. D., Scragg, R., Tayek, J. A., Valent, A. M., Walsh, J. M. E., & McCartney, C. R. (2024). Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 109(8), 1907-1947. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae290

- Ebell, M. H. (2019). Vitamin D Is Not Effective as Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease or Cancer. Am Fam Physician, 100(6), 374.

- El Amrousy, D., El Ashry, H., Hodeib, H., & Hassan, S. (2021). Vitamin D in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Clin Gastroenterol, 55(9), 815-820. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001443

- Fletcher, J., Cooper, S. C., Ghosh, S., & Hewison, M. (2019). The Role of Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanism to Management. Nutrients, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051019

- Glendenning, P., & Inderjeeth, C. A. (2012). Vitamin D: methods of 25 hydroxyvitamin D analysis, targeting at risk populations and selecting thresholds of treatment. Clin Biochem, 45(12), 901-906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.04.002

- Golden, N. H., & Abrams, S. A. (2014). Optimizing bone health in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 134(4), e1229-1243. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2173

- Goulart, R. A., & Barbalho, S. M. (2022). Can vitamin D induce remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease? Ann Gastroenterol, 35(2), 140-149. https://doi.org/10.20524/aog.2022.0692

- Granado-Lorencio, F., Blanco-Navarro, I., & Perez-Sacristan, B. (2016). Criteria of adequacy for vitamin D testing and prevalence of deficiency in clinical practice. Clin Chem Lab Med, 54(5), 791-798. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0781

- Hao, L., Carson, J. L., Schlussel, Y., Noveck, H., & Shapses, S. A. (2020). Vitamin D deficiency is associated with reduced mobility after hip fracture surgery: a prospective study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 112(3), 613-618. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa029

- Holick, M. F. (2009). Vitamin D status: measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Ann Epidemiol, 19(2), 73-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.001

- Holick, M. F. (2020). A call for action: standard of care guidelines to assess vitamin D status are needed for patients with hip fracture. Am J Clin Nutr, 112(3), 507-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa202

- Holick, M. F., Binkley, N. C., Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A., Gordon, C. M., Hanley, D. A., Heaney, R. P., Murad, M. H., & Weaver, C. M. (2011). Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 96(7), 1911-1930. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Javed, M., Althwanay, A., Ahsan, F., Oliveri, F., Goud, H. K., Mehkari, Z., Mohammed, L., & Rutkofsky, I. H. (2020). Role of Vitamin D in Colorectal Cancer: A Holistic Approach and Review of the Clinical Utility. Cureus, 12(9), e10734-e10734. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10734

- Krasowski, M. D. (2011). Pathology Consultation on Vitamin D Testing. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 136(4), 507-514.

- Kusunoki, Y., Matsui, I., Hamano, T., Shimomura, A., Mori, D., Yonemoto, S., Takabatake, Y., Tsubakihara, Y., St-Arnaud, R., Isaka, Y., & Rakugi, H. (2015). Excess 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 exacerbates tubulointerstitial injury in mice by modulating macrophage phenotype. Kidney Int, 88(5), 1013-1029. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2015.210

- Looker, A. C., Johnson, C. L., Lacher, D. A., Pfeiffer, C. M., Schleicher, R. L., & Sempos, C. T. (2011). Vitamin D status: United States, 2001-2006. NCHS Data Brief(59), 1-8.

- Madhusmita, M. (2024, October 30, 2024). Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in children and adolescents. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitamin-d-insufficiency-and-deficiency-in-children-and-adolescents

- McNamara, M., & Rosenberger, K. D. (2019). The Significance of Vitamin D Status in Breast Cancer: A State of the Science Review. J Midwifery Womens Health, 64(3), 276-288. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12968

- Mechanick, J. I., Apovian, C., Brethauer, S., Garvey, W. T., Joffe, A. M., Kim, J., Kushner, R. F., Richard, L., Pessah-Pollack, R., Seger, J., Urman, R. D., Adams, S., Cleek, J. B., Correa, R., Figaro, M. K., Flanders, K., Grams, J., Hurley, D. L., Kothari, S., . . . Still, C. D. (2019). Clinical Practice Guidelines For The Perioperative Nutrition, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of Patients Undergoing Bariatric Procedures – 2019 Update: Cosponsored By American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society For Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists *. Endocrine Practice, 25, 1-75. https://doi.org/10.4158/GL-2019-0406

- Moyer, V. A. (2013). Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med, 158(9), 691-696. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-9-201305070-00603

- NHS. (2016). Guidelines for the Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency. https://www.shropshiretelfordandwrekinccg.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/vitamin-d-guidance.pdf

- Nielsen, O. H., Hansen, T. I., Gubatan, J. M., Jensen, K. B., & Rejnmark, L. (2019). Managing vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterol, 10(4), 394-400. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2018-101055

- Pazirandeh, S., & Burns, D. (2023, September 8, 2023). Overview of vitamin D. UptoDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-vitamin-d

- Ribeiro, H. G., Dantas-Komatsu, R. C. S., Medeiros, J. F. P., Carvalho, M. C. d. C., Soares, V. d. L., Reis, B. Z., Luchessi, A. D., & Silbiger, V. N. (2021). Previous vitamin D status and total cholesterol are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry, 522, 8-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2021.08.003

- Ross, A. C., Manson, J. E., Abrams, S. A., Aloia, J. F., Brannon, P. M., Clinton, S. K., Durazo-Arvizu, R. A., Gallagher, J. C., Gallo, R. L., Jones, G., Kovacs, C. S., Mayne, S. T., Rosen, C. J., & Shapses, S. A. (2011). The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 96(1), 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-2704

- Royal Osteoporosis Society. (2020). Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Practical Clinical Guideline for Patient Management. https://theros.org.uk/media/ef2ideu2/ros-vitamin-d-and-bone-health-in-adults-february-2020.pdf

- Sahota, O. (2014). Understanding vitamin D deficiency. In Age Ageing (Vol. 43, pp. 589-591). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu104

- Sanders, K. M., Stuart, A. L., Williamson, E. J., Simpson, J. A., Kotowicz, M. A., Young, D., & Nicholson, G. C. (2010). Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 303(18), 1815-1822. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.594

- Scott, M. G., Gronowski, A. M., Reid, I. R., Holick, M. F., Thadhani, R., & Phinney, K. (2015). Vitamin D: the more we know, the less we know. Clin Chem, 61(3), 462-465. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.222521

- Scragg, R., Stewart, A. W., Waayer, D., Lawes, C. M. M., Toop, L., Sluyter, J., Murphy, J., Khaw, K. T., & Camargo, C. A., Jr. (2017). Effect of Monthly High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiovascular Disease in the Vitamin D Assessment Study : A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol, 2(6), 608-616. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0175

- Sempos, C. T., & Binkley, N. (2020). 25-Hydroxyvitamin D assay standardisation and vitamin D guidelines paralysis. Public Health Nutr, 23(7), 1153-1164. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980019005251

- Sempos, C. T., Heijboer, A. C., Bikle, D. D., Bollerslev, J., Bouillon, R., Brannon, P. M., DeLuca, H. F., Jones, G., Munns, C. F., Bilezikian, J. P., Giustina, A., & Binkley, N. (2018). Vitamin D assays and the definition of hypovitaminosis D: results from the First International Conference on Controversies in Vitamin D. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84(10), 2194-2207. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13652

- Szerszeń, M. D., Kucharczyk, A., Bojarska-Senderowicz, K., Pohorecka, M., Śliwczyński, A., Engel, J., Korcz, T., Kosior, D., Walecka, I., Zgliczyński, W. S., Wierzba, W., & Sybilski, A. J. (2022). Effect of Vitamin D Concentration on Course of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit, 28, e937741. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.937741

- Trivedi, D. P., Doll, R., & Khaw, K. T. (2003). Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. Bmj, 326(7387), 469. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469

- Ul Afshan, F., Nissar, B., Chowdri, N. A., & Ganai, B. A. (2021). Relevance of vitamin D(3) in COVID-19 infection. Gene reports, 24, 101270-101270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101270

- USPSTF. (2021). Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama, 325(14), 1436-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3069

- Vernia, F., Valvano, M., Longo, S., Cesaro, N., Viscido, A., & Latella, G. (2022). Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Implications. Nutrients, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020269

- Wallace, A. M., Gibson, S., de la Hunty, A., Lamberg-Allardt, C., & Ashwell, M. (2010). Measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the clinical laboratory: current procedures, performance characteristics and limitations. Steroids, 75(7), 477-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2010.02.012

- Wassenaar, E., O'Melia, A. M., & Mehler, P. S. (2018). Gynecologic Care for Adolescents and Young Women With Eating Disorders. Obstet Gynecol, 132(4), 1065-1066. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002903

- Weinstein, S. J., Purdue, M. P., Smith-Warner, S. A., Mondul, A. M., Black, A., Ahn, J., Huang, W. Y., Horst, R. L., Kopp, W., Rager, H., Ziegler, R. G., & Albanes, D. (2015). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D binding protein and risk of colorectal cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Int J Cancer, 136(6), E654-664. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29157

- Yuniati, T., Judistiani, R. T. D., Natalia, Y. A., Irianti, S., Madjid, T. H., Ghozali, M., Sribudiani, Y., Indrati, A. R., Abdulah, R., & Setiabudiawan, B. (2019). First trimester maternal vitamin D, ferritin, hemoglobin level and their associations with neonatal birthweight: Result from cohort study on vitamin D status and its impact during pregnancy and childhood in Indonesia. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. https://doi.org/10.3233/npm-180043

- Zhao, S., Gardner, K., Taylor, W., Marks, E., & Goodson, N. (2015). Vitamin D assessment in primary care: changing patterns of testing. London J Prim Care (Abingdon), 7(2), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17571472.2015.11493430

- Zittermann, A., Pilz, S., & Berthold, H. K. (2019). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response to vitamin D supplementation in infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical intervention trials. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01912-x

Coding Section

| Code | Number | Description |

| CPT | 82306 | Vitamin D; 25 hydroxy, includes fraction(s), if performed |

| 82652 | Vitamin D; 1, 25 dihydroxy, includes fraction(s), if performed | |

| 0038U | Vitamin D, 25 hydroxy D2 and D3, by LC-MS/MS, serum microsample, quantitative Proprietary test: Sensieva™ Droplet 25OH Vitamin D2/D3 Microvolume LC/MS Assay Lab/Manufacturer: InSource Diagnostics |

|

| ICD-10-CM | A15.0 – A15.9 | Tuberculosis |

| A19.0 – A19.9 | Military Tuberculosis | |

| A15.7, A19.0 – A19.9 | Primary or military tuberculosis | |

| C81.00 – C84.99 | Other Lymphoma | |

| C81.00 – C96.9 | Lymphoma | |

| C85.10 – C85.99 | Unspecified B-cell lymphoma | |

| C85.20 – C85.29 | Unspecified B-cell lymphoma | |

| C85.80 – C85.89 | Other specified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | |

| C85.90 – C85.99 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, unspecified, unspecified site | |

| D61.09 | Fanconi's anemia | |

| E66.01 – E66.09 | Obesity | |

| D86.0 – D86.85 | Sarcoidosis | |

| D86.86 | Sarcoid arthropathy | |

| D86.87 | Sarcoid myositis | |

| D86.89 | Sarcoidosis of other sites | |

| D86.9 | Sarcoidosis, unspecified | |

| E20.0 | Idiopathic hypoparathyroidism | |

| E20.1 | Pseudohypoparathyroidism | |

| E20.8 | Other hypoparathyroidism | |

| E20.9 | Hypoparathyroidism, unspecified | |

| E21.0 | Primary hyperparathyroidism | |

| E21.1 | Secondary hyperparathyroidism, not elsewhere classified | |

| E21.2 | Other hyperparathyroidism | |

| E21.3 | Hyperparathyroidism, unspecified | |

| E21.4 | Other specified disorders of parathyroid gland | |

| E40 – E46 | Malnutrition | |

| E64.3 | Sequelae of rickets | |

| E67.3 | Hypervitaminosis, D | |

| E72.09 | Fanconi syndrome | |

| E83.50 | Unspecified disorder of calcium metabolism | |

| E83.51 | Hypocalcemia | |

| E83.52 | Hypercalcemia | |

| E83.59 | Other disorders of calcium metabolism | |

| E84.0 – E84.9 | Cystic fibrosis | |

| E89.2 |

Postprocedural hypoparathyroidism | |

| E55.0, E83.31 – E83.32, K90.0, N25.0 | Rickets | |

| E55.9 | Vitamin D deficiency, unspecified | |

| E66.01 – E66.09 | Obesity | |

| E83.31 | Familial hypophosphatemia | |

| E83.50 – E83.59 | Disorders of calcium metabolism | |

| G73.7 | Myopathy in diseases classified elsewhere | |

| I25.1 – I25.119 | Coronary artery disease | |

| K74.3 – K74.5 | Primary biliary cirrhosis | |

| K74.60 | Cirrhosis (of liver) NOS | |

| K74.69 | Other cirrhosis of liver | |

| K90.2, Q43.8 | Blind loop syndrome, NOS | |

| K90.3 | Pancreatic steatorrhea | |

| K90.9 | Intestinal malabsorption, unspecified | |

| K83.8 |

Other specified diseases of biliary tract | |

| K90.0 | Celiac disease | |

| K91..2 | Postsurgical malabsorption, not elsewhere classified. | |

| K90.1 – K90.4, K90.81 – K90.9 | Intestinal malabsorption | |

| K90.3 | Pancreatic steatorrhea | |

| L40.0 – L40.9 | Psoriasis | |

| K50.90 – K50.919 | Regional enteritis | |

| M33.10 | Other dermatomyositis, organ involvement unspecified | |

| M60.9 | Myositis, unspecified | |

| M81.0 | Age-related osteoporosis without current pathological fracture | |

| M81.6 | Localized osteoporosis (Lequesne) | |

| M81.8 | Other osteoporosis without current pathological fracture | |

| M83.0 – M83.3 | Osteomalacia | |

| M383.5 – M83.9 | Other Osteomalacia | |

| M32.0 – M32.9 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Q78.0 | Osteogenesis imperfecta | |

| Q78.2 | Osteopetrosis | |

| N20.0 – N22, N13.2 | Renal, ureteral, urinary calculus | |

| N18.3 – N18.6 | Chronic Kidney Disease III-V, ESRD | |

| N25.0 | Renal osteodystrophy | |

| P71.0 – P71.1 | Neonatal hypocalcemia | |

| Q78.0 | Osteogenesis imperfecta | |

| Q78.2 | Osteopetrosis | |

| Z33.1 – Z33.3 | Pregnant state, incidental | |

| Z3A.00 – Z3A.49 | Weeks of gestation | |

| Z34.00 – Z34.93 | Encntr for suprvsn of normal first pregnancy, unsp trimester (Encounter for supervision of normal first pregnancy, unspecified trimester) | |

| Z79.2 | Long term (current) use of antibiotics | |

| Z79.899 | Other long term (current) drug therapy |

Procedure and diagnosis codes on Medical Policy documents are included only as a general reference tool for each policy. They may not be all-inclusive.

This medical policy was developed through consideration of peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community, U.S. FDA approval status, nationally accepted standards of medical practice and accepted standards of medical practice in this community and other nonaffiliated technology evaluation centers, reference to federal regulations, other plan medical policies and accredited national guidelines.

"Current Procedural Terminology © American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved"

History From 2016 Forward

| 01/15/2025 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating description, policy state #3 for clarity, note #1 and #2, rationale and references. |

| 01/25/2024 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating description, table of terminology, rationale and references. |

| 01/26/2023 | Annual review, updating policy for clarity and consistency. Adding verbiage to guidelines regarding bariatric procedures. Also updating description, rationale and reference. |

| 08/08/2022 | Interim review, updating policy for clarity. Also updating description, rationale, and references. |

| 01/11/2022 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating rationale and references. |

| 01/05/2021 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating description, rationale and references. |

| 04/08/2020 |

Interim review to add Z79.2 to the policy. No change to policy intent. |

| 01/06/2020 |

Annual review, updating guidelines and coding. No change to policy intent. |

| 05/23/2019 |

Corrected typo to coding |

| 01/08/2019 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating ICD coding. |

| 01/22/2018 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 08/21/2017 |

Updated coding. No other changes. |

| 08/09/2017 |

Updated coding. No other changes. |

| 06/19/2017 |

Updated coding section. No other changes. |

| 04/26/2017 |

Updated category to Laboratory. No other changes made. |

| 01/04/2017 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 01/05/2016 |

NEW POLICY |